For decades, cancer diagnosis has followed a familiar pattern: symptoms appear, scans confirm abnormalities, and treatment begins. But artificial intelligence is beginning to disrupt this reactive model, shifting medicine toward something far more powerful — prediction and prevention.

In a recent conversation on the BBC’s AI Decoded, Professor Regina Barzilay, one of the world’s leading figures in artificial intelligence and cancer research, described a pivotal realisation: AI could play a much bigger role in identifying cancer risk long before the human eye can detect it. Her insight emerged from a deeply personal and scientific journey — recognising that cancer detection is, at its core, a prediction problem.

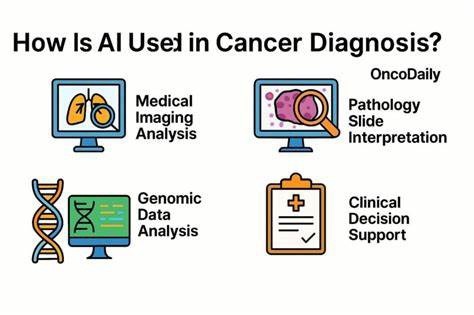

Traditional medical imaging relies heavily on human interpretation. Radiologists examine mammograms, scans, and biopsies, looking for visible signs of abnormality. But the human eye has limits. Subtle cellular or structural changes often remain invisible until the disease has progressed. AI systems, however, can analyse vast datasets of medical images and detect patterns too complex, too faint, or too gradual for humans to recognise.

In breast cancer screening, this capability is transformative. AI models can review historical mammograms and identify micro-changes that signal future cancer risk years before a tumour becomes visible. This means that what once appeared to be a “normal” scan may actually contain early warning signs — signals that only machine intelligence can decode.

The implications extend beyond technology into policy and public health. One of the most debated questions in medicine today is: at what age should women begin routine mammograms, and how frequently should they be screened? Different countries and professional bodies offer conflicting recommendations — annually, biennially, or starting at different ages. These guidelines are based on population-level statistics, not individual risk.

AI changes that equation.

Instead of relying on broad averages, AI-driven diagnostics could personalise screening schedules. A woman identified by AI as high-risk might begin screening earlier and more frequently, while someone at lower risk might avoid unnecessary tests. This shift from one-size-fits-all medicine to precision prevention could reduce mortality, optimise healthcare resources, and minimise the psychological and physical costs of overdiagnosis.

Crucially, the science of cancer has not changed overnight. The biological mechanisms were always there. What AI brings is a new lens — the ability to interpret complex biological signals at scale and speed. Machines can “see” colour gradients, structural anomalies, and statistical patterns that humans simply cannot distinguish reliably.

Yet this is not about replacing clinicians. It is about augmenting human expertise with computational intelligence. The future of cancer diagnosis lies in collaboration: doctors providing clinical judgment and empathy, AI delivering unprecedented analytical power.

We are standing at the threshold of a new era in medicine — one where cancer may be identified not when it is visible, but when it is still forming. If harnessed responsibly, artificial intelligence could redefine not only how we diagnose cancer, but how we understand risk, prevention, and the very timeline of disease itself.

In that sense, AI is not just a technological upgrade. It is a paradigm shift — from reacting to illness to anticipating it. And in the fight against cancer, anticipation may be the most powerful tool humanity has ever had.