When China unveiled its latest humanoid robot showcase, the reaction across the West was immediate: awe, disbelief, and unease in equal measure. The fluidity of movement, the balance, the synchronised choreography — these were not stiff, experimental prototypes. They were machines that looked commercially ready. And that perception, more than the spectacle itself, has triggered a serious strategic rethink in Washington, Brussels and beyond.

For years, Western commentary framed humanoid robotics as futuristic — impressive demos, yes, but commercially distant. China’s display challenged that assumption. The flexibility of the robots — bending, sprinting, flipping, coordinating — suggested a maturity many assumed was still years away. What startled observers most was not just the performance, but what followed: the sales numbers.

In 2025, Chinese manufacturers dramatically outpaced their American counterparts. Unitree reportedly sold 5,500 humanoid units. AGIBOT followed with 5,100 units. UBTECH sold 1,000. Leju Robotics moved 500. EngineAI delivered 400. Fourier Intelligence added another 300.

Compare that to the United States. Figure AI sold 150 units. Agility Robotics sold 150. Even Tesla, with all its manufacturing pedigree and global brand recognition, reportedly sold just 150 humanoid robots. All other non-listed global players combined accounted for only 1,350 units.

The implication is stark: China is not merely experimenting. It is scaling.

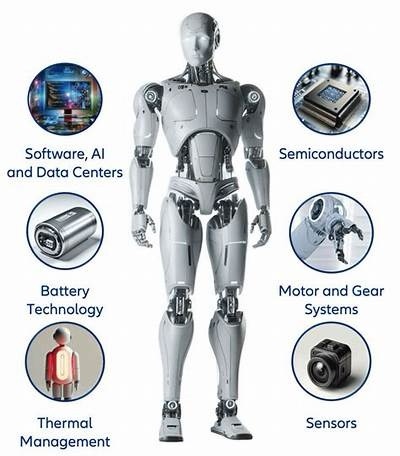

Western analysts are now grappling with what this means. Robotics is not just another consumer tech category. Humanoid robots intersect with manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, defence, elder care, retail, and domestic services. The country that achieves scale first gains not only economic leverage but supply chain dominance, data accumulation advantages, and standards-setting power.

China’s advantage appears structural. State-backed financing, vertically integrated supply chains, access to rare earth materials, rapid prototyping ecosystems, and massive domestic demand create a flywheel effect. The West, by contrast, remains fragmented — innovative but slower to industrialise breakthroughs.

There is also the psychological factor. For decades, the United States was seen as the unquestioned leader in frontier technologies. The robot showcase challenged that narrative. Much like previous moments in space exploration or semiconductor manufacturing, this display felt symbolic — a signal that the centre of gravity in advanced manufacturing may be shifting.

Yet caution is warranted. Unit sales alone do not determine long-term dominance. Quality, reliability, AI integration, regulatory frameworks, and international trust will all shape outcomes. American firms still lead in foundational AI research, advanced chip design, and venture-backed innovation ecosystems. Europe retains strength in precision engineering.

However, what the West cannot ignore is speed. China appears willing to deploy early, iterate fast, and refine in the field. If humanoid robots become as economically transformative as smartphones or industrial automation, early scale could lock in network effects.

The viral robot show was more than entertainment. It was a geopolitical message. It demonstrated that humanoid robotics is moving from lab curiosity to commercial reality — and that China may already be miles ahead in deployment.

The Western reaction — admiration mixed with alarm — suggests policymakers understand what is at stake. The next decade will reveal whether this moment was a temporary surge or the beginning of a sustained technological realignment.