For two decades, Jensen Huang built Nvidia into the company powering the AI revolution. Its chips became the beating heart of data centres training large language models and running generative AI systems used by hundreds of millions worldwide. But Huang understands something critical: the next phase of AI will not live solely in hyperscale data centres. It will live at the edge.

Autonomous cars, drones, robotics, AI wearables, and industrial systems cannot wait for instructions to travel to a distant cloud server and back. Decisions must happen in milliseconds. That shift demands infrastructure capable of processing AI workloads directly at the source — inside the network itself.

This is where Nokia re-enters the global stage.

The telecom industry is a $3 trillion ecosystem with millions of base stations deployed worldwide. Yet for years, those towers were designed primarily to move data, not think. Nvidia had tried convincing vendors to rebuild networks around its architecture, but legacy systems — particularly those deeply integrated with traditional chip providers — made radical redesign nearly impossible.

Nokia was different.

Architecturally, it was the only major Western vendor capable of adapting without tearing everything apart. Its infrastructure design allowed AI workloads to run inline on Nvidia hardware. Seeing the opportunity, Huang made a decisive move: a $1 billion investment in Nokia, becoming its second-largest shareholder. This was not a passive financial stake. It was a strategic declaration.

Nvidia had the chips. Nokia had the towers.

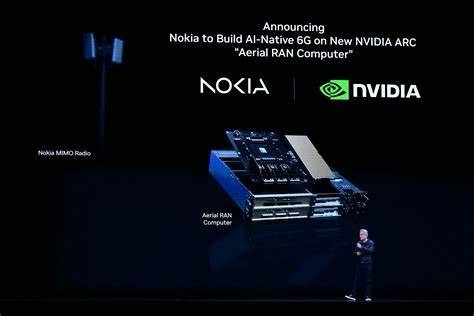

Together, they aim to build AI-powered cell towers — infrastructure that doesn’t just transmit data but processes it. Embedding AI into base stations transforms networks in two profound ways.

First, it optimises today’s systems. AI-enabled towers can dynamically manage signal loads, reduce latency, and cut energy consumption by as much as 30 percent. In a world where hundreds of millions rely on mobile AI tools weekly, responsiveness matters. Networks must adapt in real time.

Second, it prepares for what’s coming. The next generation of AI assistants, autonomous machines, and real-time decision systems cannot depend on faraway data centres. Edge-based AI networks could deliver responses in tens of milliseconds — the threshold required for physical AI systems operating in motion.

Markets responded immediately. Nokia’s stock surged 22 percent in its largest single-day gain since 2013. Early customer trials are already scheduled for 2026, with analysts projecting the AI-RAN market could exceed $200 billion by 2030.

Yet the deeper story is not about a single partnership. It is about survival through reinvention.

In 2013, Nokia sold its handset business to Microsoft for $7.2 billion — a decision widely criticised at the time. Two years later, Microsoft wrote off $7.6 billion on that same business. Nokia had exited before total collapse.

Instead of clinging to its fading identity, Nokia invested €15.6 billion acquiring Alcatel-Lucent, doubling down on network infrastructure. It pivoted not to something new, but to something it had quietly maintained for years.

The asset that saved Nokia wasn’t built in crisis. It was hidden in plain sight.

The Nokia 3310 became legendary for its durability. The company behind it may prove even more resilient. If Huang’s bet succeeds, Nokia will not merely remain relevant — it could become the backbone of physical AI, the invisible infrastructure enabling machines to think in real time.

The company that lost the smartphone war may yet win the AI infrastructure age.