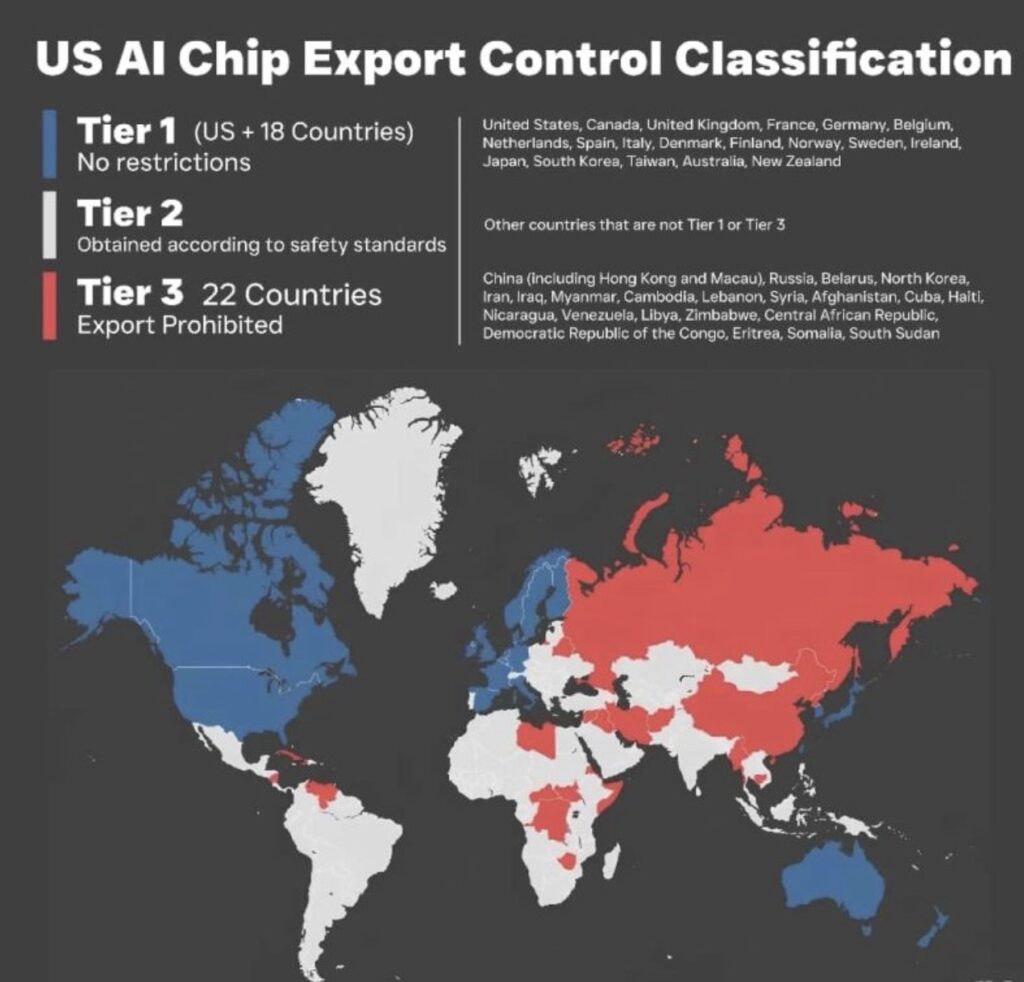

The United States’ decision to allow Nvidia to export its powerful H200 chip to China marks a notable recalibration in technology policy. After years of tightening export controls on advanced semiconductors, this move suggests a more nuanced approach—one that balances national security concerns with economic realities and global technological momentum.

At a technical level, the H200 represents the cutting edge of AI infrastructure. Designed to accelerate large-scale machine learning models, data analytics, and high-performance computing, the chip is a cornerstone of modern AI development. Allowing Chinese firms access to this capability will almost certainly accelerate AI research, cloud services, and industrial automation within China. While this may narrow the AI performance gap between US and Chinese firms, it also reinforces a global truth: innovation ecosystems rarely thrive in isolation.

For Nvidia, the implications are commercial as much as strategic. China remains one of the world’s largest markets for data-centre hardware and AI acceleration. Restricting access entirely would not only reduce revenue, but potentially encourage domestic Chinese alternatives to mature faster. By permitting controlled exports, the US preserves leverage over standards, architectures, and future dependencies—arguably a more effective long-term strategy than outright technological decoupling.

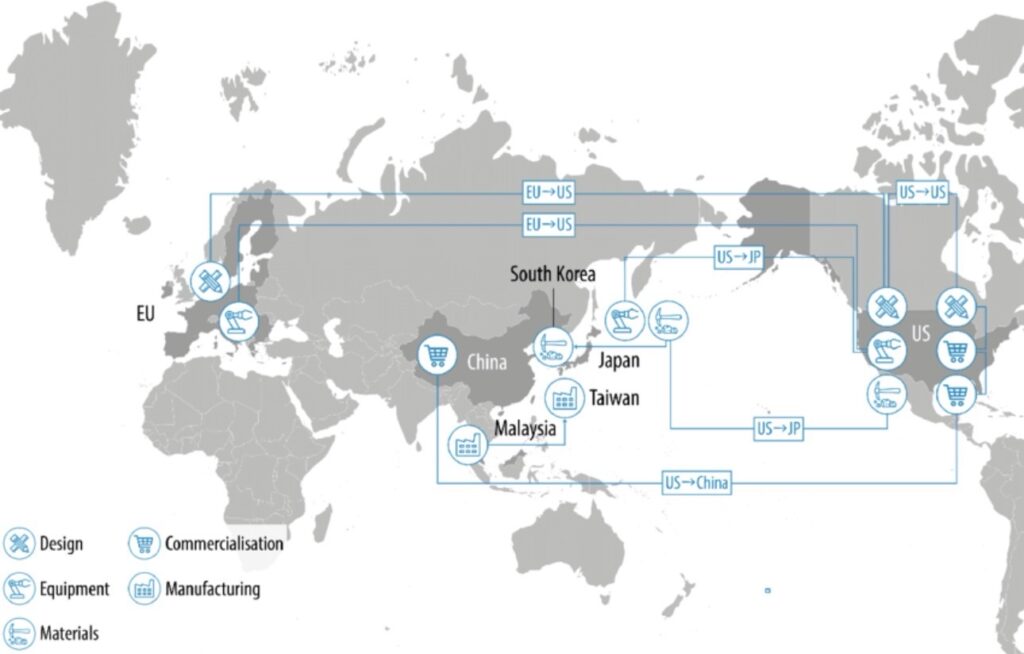

However, the supply-chain dimension is where the stakes become truly global. Nearly all of Nvidia’s most advanced chips are fabricated by TSMC, based in Taiwan. This geographic concentration is one of the most significant structural vulnerabilities in the modern technology economy. Advanced logic chips—whether destined for Silicon Valley, Shenzhen, or Frankfurt—depend on a single manufacturing ecosystem that is both technically unparalleled and geopolitically exposed.

China’s long-stated ambition to bring Taiwan under its control adds a layer of strategic tension to every semiconductor policy decision. Allowing H200 exports could be interpreted as a form of pragmatic cooperation: an acknowledgment that interdependence, rather than absolute exclusion, may help stabilise an otherwise brittle relationship. If China continues to rely on Taiwanese fabrication and US-designed architectures, the incentive to preserve the status quo arguably increases—at least in the short to medium term.

That said, this policy shift does not eliminate risk; it redistributes it. By keeping Chinese AI development partially tied to US firms and Taiwanese manufacturing, the global system remains efficient but fragile. Any disruption—whether from military escalation, sanctions, or natural disaster—would ripple instantly across global markets, affecting everything from cloud computing to automotive production.

There is also a competitive paradox at play. Enabling access to powerful chips like the H200 may accelerate Chinese innovation, but it also reinforces US leadership in chip design, software ecosystems, and AI frameworks. Nvidia’s dominance is not merely about silicon; it is about CUDA, developer tooling, and deep integration across industries. From this perspective, controlled openness may extend American technological influence rather than diminish it.

In the longer term, this decision underscores the urgency of supply-chain diversification. Efforts to expand advanced manufacturing in the US, Europe, and allied nations will continue, but replicating Taiwan’s expertise will take years, if not decades. Until then, policies like this one reflect a world navigating interdependence rather than escaping it.

Ultimately, allowing Nvidia’s H200 exports to China is less a concession than a recognition of reality. Technology leadership today is not enforced solely through restriction, but through strategic engagement, resilient supply chains, and the careful management of shared dependencies. In a world where the most powerful chips come from a single island, cooperation—however uneasy—may be the least risky option available.